Review: Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress by Dai Sijie

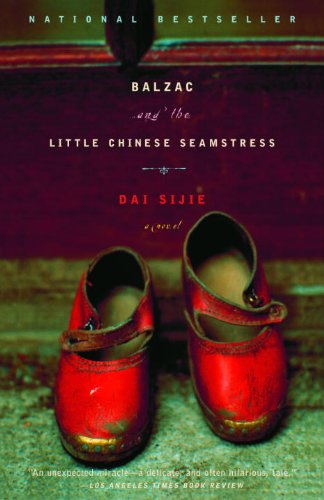

The princess of Phoenix mountain wore pale pink canvas shoes, which were both sturdy and supple and through which you could see her flexing her toes as she worked the treadle of her sewing machine. There was nothing ordinary about the cheap, homemade shoes, and yet, in a place where nearly everyone went barefoot, they caught the eye, seeming delicate and sophisticated…

Thus Dai Sijie introduces the pivot of the eternal triangle in Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress. Her sewing machine (which the narrator breathlessly informs us, was Made in Shanghai) is equal to her capable feet in their pink shoes in attracting Luo and the narrator, two young men who occupy the other points of the triangle.

References to shoes and feet are everywhere in the book. Luo convinces the little seamstress in their first meeting to remove a shoe, revealing that, like his, her second toe is longer than the first. At one point, the seamstress suddenly changes her footwear from pink canvas to tennis shoes, “white as chalk.” A suitcase which turns out to contain the treasure of banned books is described as “soft, supple, and smooth to the touch… [making] me think at once of a lady’s doeskin shoe.”

Luo and his narrator friend have been exiled from the world of books and education which they have just begun to taste. Maoist reeducation sent thousands of high school graduates and university students to live in peasant villages, forbidding them books other than the little red book of Mao’s sayings. As they struggle to adapt to the bleak life of work, they yearn for the freer life of the imagination.

The young intellectuals are not the only Chinese with these yearnings. When the village headmaster discovers Luo’s ability to relate a story, he decides to send the two each month to the cinema, so that they can bring the stories back and perform them for the village. The narrator can play the violin, and even convinces revolutionary inspectors that Mozart was a fine revolutionary thinker, suitable for village ears.

But eventually, in their rivalry for the little seamstress, they woo her with stories gleaned from the pages of Balzac and Dumas. They believe they are seducing the seamstress to accept one of them. The poignant result of this effort is both delightful and unexpected.

At 184 pages, the book is a novella in length, entirely suitable for a long evening by the fire, or to while away time on a plane or train trip. I recommend it to anyone who is horrified at the idea of exile in a desert of no books.

No comments:

Post a Comment