Review: Meritropolis by Joel Orman and The Home by Eric Tripp

Home and imprisonment are recurring themes in YA novels, and so are the concepts of feeling loved and valued. By chance, I purchased two books together that explore these ideas, and since I read them together. I decided to review them in the same post.

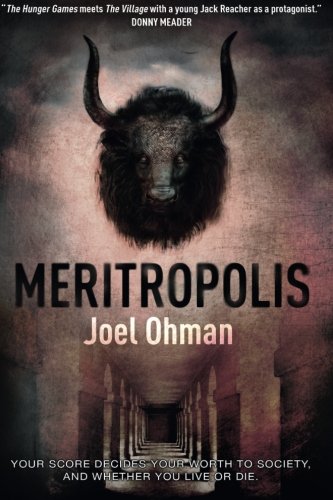

Meritropolis

This novel is post-apocalyptic dystopian, set in a world with bizarre and hostile mutations that merge animals in obviously deliberate ways. The bion is a bison-lion combination, for example, a vicious meat-eating, bull-stubborn giant with a devil-red pelt and eyes. The snick is a winged bloodsucker formed from the genes of a snipe and a tick; it flies in flocks and can drain its victims dry. Chimpzelles, merging chimps with gazelles, hunt in tribal groups with primitive hand-weapons, and will devour humans as happily as any other prey.Holding these hostile hordes at bay, Meritropolis itself is a walled city in which citizens have carefully-defined roles that rise from their measured merit: each citizen receives a periodically-reassessed Score that determines whether they will be permitted to stay in the city. Since it is accepted that being outside the wall at night is fatal, getting a low Score is a death sentence.

That's what happened to Charley's brother. Charley is stunned by the verdict, especially when his own Score turns out to be high. It has left him burning with anger against the city management, motivated to do well in warrior tests, and questioning the fairness of the whole Score assessment system. In short, he is messed up.

The way Charley fits himself into the system to discover its problems and its value to him is the only way his high Score is obvious; in every other way, his behavior and choices only reveal him as a disturbed adolescent. The flow of the story is not helped by the many other voices sharing its narration, none of which are clearly distinguishable from Charley's.

Nevertheless, the novel's unrelenting physical and philosphical action, and its high concept and creative world-building, serve to offset these minor issues of technique. It is a very enjoyable read.

Liner Note: The book's title was a tongue-twister until I recalled the Fritz Lang classic film, Metropolis. Suddenly it began to fall more naturally on my reading ear.

The Home

The concept for The Home was promising enough that I nominated it for publishing on Kindle Scout: hundreds of children are tended in a single building by their "Father," who either kidnapped them or coaxed them off the streets as runaways.These children don't work like Fagin's crew, nor do they go to school. They seem to spend their time playing video games and earning tokens by doing chores or gambling. The carny atmosphere doesn't disguise the fact that none of them are allowed to leave. Think of boys-becoming-donkeys on Pleasure Island in Pinocchio, and you've got the vibe.

The tale is told by two voices: Bom and Mystic are older children in the Home. Bom is a natural leader, a young man in age, who is being groomed as a sort of deputy-Father. Mystic is a new addition to the ranks—who incidentally, also fills the author's need of a foil for explanations. (In '50s pulp science fiction, for example, this role was filled by a buxom blonde lab assistant.)

In the only subtle concept of the novel, the Home itself becomes a representation of many inner-city societies, with a "welfare class" trapped in sterile leisure by a benign but strict provider, and an upwardly-mobile (or "outwardly-mobile") group seeking a way to live on their own terms.

By contrast to Meritropolis, this novel was dismayingly simplistic and badly proof-read, with an annoying number of grammatical and typographical errors. The most distressing "typo" left me looking for an escape with the same fervor as Bom and Mystic. The word is in quotes because its near-universal occurrence indicates it was a writer's or proofer's error of knowledge rather than a mistake in typesetting: the omission of commas before every name used as a directed address in dialog. It was never "I was looking for that, Bom..." but Watch out! Duck!:

"I was looking for that Bom..."

About halfway through, I stopped noting error corrections in my Kindle, especially as a frequent use of the wrong homophones made me suspect this was a novel written using speech software. Mispronounced words or sloppy pronunciations might have yielded some of the more amusing choices: "crown" for "crayon" for example.

Since I understand such systems ask the speaker to select among homophones like "you're" and "your" or "rain" and "reign," there was an opportunity to correct it. It is more likely someone simply accepted the most-frequent default without looking at the options. Either way, in writing The Home using speech software, the author made another wrong choice.

No comments:

Post a Comment