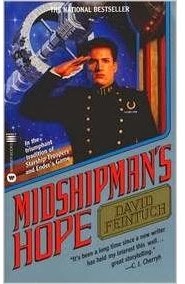

Feintuch gives the words to Ibn Saud, a passenger on the interstellar ship Hibernia, speaking to the midshipman of the title, Nicholas Seafort:

And so we have the anomaly of a great starship, the pinnacle of technology, governed by an authoritarian system not unlike that of the eighteenth century sea navies.As I read these words again, I was struck by how many of my favorite stories build upon the naval metaphor as a microcosm of society, or to express the structure of the society as a whole. While such science fiction novels rarely, as Feintuch does in this series, delve into the author's (or "society's") reasons for choosing the discipline-taut, tradition-rigid authoritarianism of the Georgian-era navy to govern a starship, they all share that structure as a basis for their stories.

Bildungsroman with a naval metaphor usually focus on the development of a youth who begins as a ship's boy, cadet, or midshipman, although occasionally they begin deeper below deck, and follow an older "ordinary seaman" or crewhand. They range from literary classics like C.S. Forester's Hornblower Saga, which begins with Mr. Midshipman Hornblower; and science fiction classics like Alfred Bester's The Stars My Destination; to juveniles like the David Birkenhead series by Phil Geusz, which commences with Ship's Boy; and epic science fiction like the outstanding Honor Harrington series, in which the first novel finds David Weber's eponymous heroine On Basilisk Station as a disgraced captain, but tells the back story of her days as cadet, ensign and commander in the course of the novel.

What do they share in common?

- In each, an exceptional person begins from a position of inequity with the overall authority, and develops to become a peer or leader in that structure

- Where introspective, the protagonist questions his/her ability to achieve what is needed to progress; where not introspective, as with Bester's Gully Foyle, he/she simply accepts the inequity as a fact of life and does not initially try to overcome it

- Whether authority is paternal (David Birkenhead's Lord Marcus or Harrington's Admiral Raoul Courvousier); martinet (notably, some of the captains under whom Honor Harrington served in her backstory); or simply indifferent in applying the regulations (as with Gully Foyle's unnamed captain on S.S. Nomad), its end result is the growth of the protagonist. Each becomes better able to function as a crewmember, officer or captain on their ship, or a better, more productive member of society.

As I enjoy the Seafort Saga again, I am reminded on this day of the way in which a real navy was nearly defeated at the outset of America's entry into WWII, and that eventually that navy surmounted the disastrous day of December 7, 1941.

The discipline, tradition, and culture of that navy could not be sunk with a few battleships in Hawaii. And that is a metaphor worth contemplating.

No comments:

Post a Comment