|

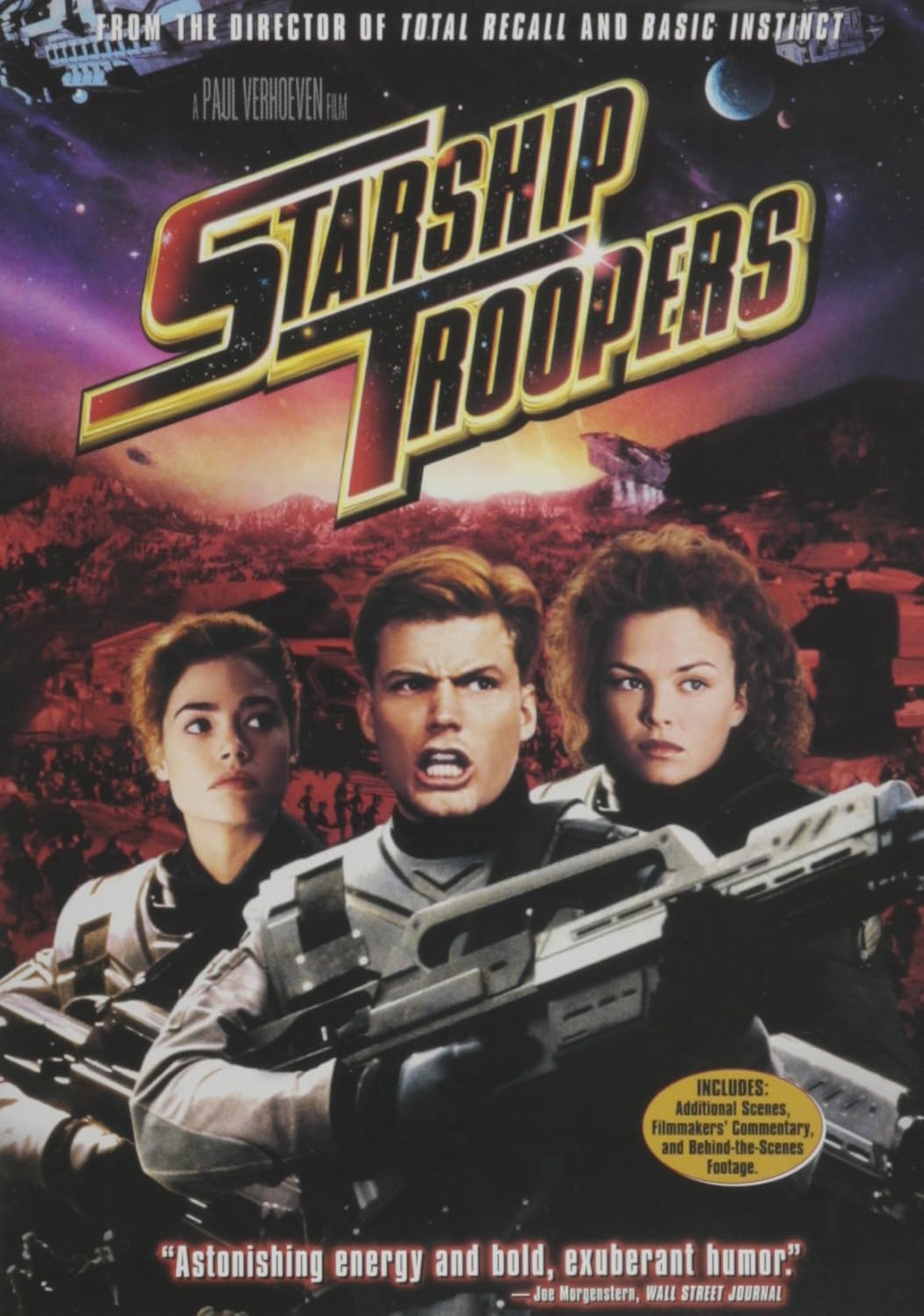

| Original DVD Cover Image, 1998 |

Review: Starship Troopers with Casper van Diem, Michael Ironside vs. Starship Troopers by Robert A. Heinlein

Challenged to name a movie that fell disappointingly short of its source, my first reaction is Starship Troopers, out in a 20th anniversary edition this month.

Two decades ago, I was tremendously excited when I learned they would make this book into a movie, even as I doubted they would capture its flavor in full. The problem is internal dialogue. Truly interesting books take us into the inner life of their main characters; in revealing those meditations and self-recriminations, they expose their souls.

Two decades ago, I was tremendously excited when I learned they would make this book into a movie, even as I doubted they would capture its flavor in full. The problem is internal dialogue. Truly interesting books take us into the inner life of their main characters; in revealing those meditations and self-recriminations, they expose their souls.

Without that insight, fictional characters are as intellectually interesting as rock-em-sock-em robots.

Typically, movies substitute external dialogue and narrative for these inner debates. An example of this done well can be seen in the 1984 version of Dune. Without the narrative voiced by Gurney Halleck (Patrick Stewart) and Princess Irulan (Virginia Madsen) in that film, its story would be impenetrable. With it, and by dint of voicing much of the book’s mental dialogue, it succeeds as an adaptation.

So I knew it would not be impossible to capture the philosophy- and social-commentary-laden substance of Heinlein’s novel. Then I saw it in the theatrical release, and was sorely disappointed. This is simply not Heinlein’s story.

Oh, the bugs are there. The sneak attack by this alien hive-dwelling race that wipes out Johnny Rico’s home city is in the movie. The Mobile Infantry are there, with their armored suits complete with heads-up displays, pocket nukes and jump jets. What didn’t survive the cut? Only the reason why Johnny joins the service in the first place.

Heinlein’s novel hinges on two social differences in the world of Starship Troopers. First, only veterans—those who have chosen to place their lives “between their loved home and the war’s desolation”—have the right to vote. Civilians do not have that right, and neither do serving troopers. Heinlein justifies this very succinctly:

Typically, movies substitute external dialogue and narrative for these inner debates. An example of this done well can be seen in the 1984 version of Dune. Without the narrative voiced by Gurney Halleck (Patrick Stewart) and Princess Irulan (Virginia Madsen) in that film, its story would be impenetrable. With it, and by dint of voicing much of the book’s mental dialogue, it succeeds as an adaptation.

So I knew it would not be impossible to capture the philosophy- and social-commentary-laden substance of Heinlein’s novel. Then I saw it in the theatrical release, and was sorely disappointed. This is simply not Heinlein’s story.

Oh, the bugs are there. The sneak attack by this alien hive-dwelling race that wipes out Johnny Rico’s home city is in the movie. The Mobile Infantry are there, with their armored suits complete with heads-up displays, pocket nukes and jump jets. What didn’t survive the cut? Only the reason why Johnny joins the service in the first place.

Heinlein’s novel hinges on two social differences in the world of Starship Troopers. First, only veterans—those who have chosen to place their lives “between their loved home and the war’s desolation”—have the right to vote. Civilians do not have that right, and neither do serving troopers. Heinlein justifies this very succinctly:

Suddenly he pointed his stump at me. “You. What is the moral difference, if any, between the soldier and the civilian?” ”The difference,” I answered carefully, ” lies in the field of civic virtue. A soldier accepts personal responsibility for the safety of the body politic of which he is a member, defending it, if need be, with his life. The civilian does not.”

Second, it is anyone’s choice to enlist at any time after their 18th birthday. The services will find something for the enlistee to do, to allow them to earn the franchise. But if they then go AWOL, resign, or are drummed out for any reason, they never have the opportunity to try again. Politicians from dogcatcher to President must, under this system, be veterans, and there are no “reserves”.

The movie barely mentions either of these two critical concepts. Worse, the main source informing Rico’s choices, his high school “History and Moral Philosophy” teacher, Col. DuBois (who pointed his stump at Johnny in the quote from the novel), is barely there in the first scenes, and not mentioned again. These ideas are presented in hit-and-miss fashion, as if they are part of the recruit training after enlistment, instead of why recruits choose to enlist in the first place.

Moving the important motivation to enlist into the recruit training has another consequence—we do not get a real sense of the conflict between Rico and his father. As a result, his reaction when his home city is attacked is shallow. He’s now an orphan, okay, move on. This robs the viewer of one of the most poignant scenes Heinlein has written, when as an officer, Rico is relying on his master sergeant.

Lieutenant Rasczak (Michael Ironside) is given most of the lines that Col. DuBois has in the novel. So we get a tepid, PC-diluted “Violence has resolved more conflicts than anything else. The contrary opinion that violence doesn’t solve anything is merely wishful thinking at its worst,” instead of

Anyone who clings to the historically untrue—and thoroughly immoral—doctrine that “violence never settles anything” I would advise to conjure the ghosts of Napoleon Bonaparte and the Duke of Wellington and let them debate it. The ghost of Hitler could referee, and the jury might well be the Dodo, the Great Auk and the Passenger Pigeon. Violence, naked force, has settled more issues in history than has any other factor, and the contrary opinion is wishful thinking at its worst. Breeds that forget this basic truth have always paid for it with their lives and freedom.

If this was the only shortcut, I would not complain. It is not. Sergeant Zim is another crucial character whose best lines from the book are given to Lt. Rasczak, or simply omitted. Rico’s relationship with training sergeant Zim is formative for him. Again, the movie simply ignores this part of the story.

In addition, the movie completely omits Juan Rico’s choice to go to officer training, and how this perspective changes his assessment of his life and responsibilities. I can see leaving this out to save time (and provide grist for a sequel). I suspect, however, that the movie’s creators were simply in a hurry to confront Rico with the alien bugs.

The other changes are minor, and do not, in my opinion, ruin the story. In Heinlein’s novel, women do not serve in the Mobile Infantry; Heinlein was a product of his time and served as a Naval officer in the 40s. He does give women a unique role that men cannot, for the most part, perform as well. In addition, Johnny’s best friend Carl does not end up as a commanding colonel in the novel—to describe where he does would be a spoiler. But these are minor changes, and I can roll with them.

What I miss are the thoughts about why defensive war is necessary, and how best to conduct a war once one is begun. Once again, the words are those of Col. DuBois:

If you wanted to teach a baby a lesson, would you cut its head off?… Of course not. You’d paddle it. There can be circumstances when it would be just as foolish to hit an enemy city with an H-bomb as it would be to spank a baby with an axe. War is not violence and killing, pure and simple; war is controlled violence, for a purpose. The purpose of war is to support your government’s decisions by force.

Dune has been remade, and the second version has qualities that the first did not. I cling to the hope that Starship Troopers will be remade by someone with the vision to see past the great special effects opportunity to create a movie worthy of the power of Robert Heinlein’s novel.

In the meantime, skip the movie. Read the book.