Review: Quicksilver by Neal Stephenson

Remember Randy Waterhouse, the protagonist of Stephenson's Cryptonomicon? Book One of this trilogy introduces his 17th-century ancestor Daniel, a complex character intimately enmeshed with the major controversies of his day.

Quicksilver

As a child, Daniel Waterhouse witnessed the death of the King of England with the coming of Oliver Cromwell and the Roundheads. As a youth, he attends the re-emergently Catholic Cambridge, rooming with a young Isaac Newton and studying “natural philosophy” instead of preparing for the Apocalyse his father expects in the year 1666. But instead of the end of days, Daniel meets the Black Plague in that year, and watches his father die in the Great London Fire.

And we know that in later years, this pilgrim does finally go to the New World, where he starts the Massachusetts Bay Colony Institute of Technological Arts, and intrigues a young boy named Ben (Franklin) into scientific inquiries. (Actually, the book opens on the seventy-plus year old Waterhouse in Massachusetts, and the rest of the story is told as flashbacks interspersed with “current day” journeys. This is the same Innis-mode technique Stephenson used in Cryptonomicon.)

Quicksilver is shot through with references to mercury—I counted twenty-three overt occurrences in the first few chapters. The quicksilver theme brings together communications (Mercury was the messenger of the gods), natural philosophy, alchemy and chemistry (mercury is an important element to all three), medicine (Mercury’s symbol was used by physicians, and elemental mercury was often prescribed), and war (Hg was an essential ingredient in explosives of the day).

Daniel Waterhouse explores his belief in religious free will against the background of revolutions in science, mathematics, cryptography, religion and politics. Like drops of mercury on a heated plate, he ranges far and wide, and reflects the brilliance of those around him.

King of the Vagabonds

Bobby Shaftoe went to sea,

Silver buckles on his knee.

He’ll come back to marry me.

Mother says so!

Half-Cocked Jack Shaftoe is the eponymous King of the Vagabonds in Book Two, and easily the most likable character in the novel. Here is where Quicksilver swings into adventure-mode, as Jack gallivants across the Holy Roman Empire, liberating damsels in distress and rescuing the odd coin or two—or vice versa.

Like the other principals, his life is intertwined with Liebnitz’, and serves as well to illustrate the mathematician-philosopher’s other vocation: mining engineer. Like Isaac Newton (as well as Thomas Jefferson and Ben Franklin), Liebnitz was a wildly productive genius whose efforts spanned nearly all of the industries and intellectual pursuits of his time.

Half-Cocked Jack is almost his antithesis, preoccupied with getting and spending his gains, ill-gotten and virtuous alike. As such, Jack is much closer to the Bobby Shaftoe of the nursery rhyme than is his g-great-grandson Bobby in Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon.

Odalisque

Book Three centers around the activities of the harem girl rescued in the relief of Vienna by Shaftoe in Book Two. Eliza has come a long way from the slave trudging across Europe at Jack’s heels. She is becoming a wealthy woman through her understanding of the Byzantine commodities market—and a chance meeting with Liebnitz that supplies her with the essential ingredient for wealth-building then (and today), a truly unbreakable cipher.

Historically, Liebnitz was known to have been fascinated by the I Ching, and to have used it as a cipher key to encode personal correspondence. Stephenson has incorporated the political backgrounds and historical battlefields, the customs and entertainments of the late 17th and early 18th centuries, to flesh out the first part of his tale of the (historical) scientific rivalry between Liebnitz and Newton, and the rise of the (fictional) Societas Eruditorum.

As with the first two books, Odalisque is shot through veins of mercury. This section adds numerous references to Minerva as the patron of Amsterdam, model for scientists, and goddess of wisdom and guile.

Together, these three books weave a wonderful trio of mercuric systems to presage the coming system of the world. But before we can arrive at his system, we must first work our way through The Confusion, the next in Stephenson's set of historical science-fiction trilogies.

Liner Notes:

- Intrigued by the Baroque Cycle and where it intersects history and reality? Check out the Metaweb.

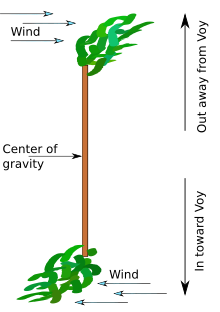

- Jane Chords: Enoch wind. Mother died. Like Daniel.